What Really IS The Future of Publishing?

Good morning!

Welcome to this week’s edition of Are You Engaged? A quick note before I begin. I’ll be taking next week off for some personal reasons but will be back to the regular schedule on June 3rd. This week, I’ll be going very long in the A Little Bit of Culture section so consider this something of a “double issue.”

Now, for Your Weekly Rundown.

Your Weekly Rundown

Last week was brutal. The main story, of course, was the major layoffs that took place across the media industry. NiemanLab pretty much sums everything up in their piece from last Friday. Condé Nast, Vice, The Economist, Quartz, and BuzzFeed either all announced layoffs and furloughs, or started them outright. Hundreds of media jobs were lost in the span of a few days, leaving many to wonder what happens next. (We’ll get to some of that wondering in a little bit.) There’s honestly not much more that I can say at this point. Watching so many hardworking writers, reporters, editors, and (most likely) unheralded production and operation teams lose their jobs is devastating.

There were also reports that TheMaven, the company that owns Sports Illustrated, is running out of money. According to the information currently available, Sports Illustrated only has 11 months of operating funds remaining. TheMaven is actively looking to raise money to keep the company running. This news comes after Sports Illustrated had to cut nine percent of its staff in March, including the very public firing of Grant Wahl.

In something that maybe resembles positive news, on May 12th, The Guardian reported that a local group was working on a deal to buy The Baltimore Sun (shouts to my fellow Season Five of The Wire die hards out there—Gus Haynes for life!) from its current owner Tribune Publishing, which also just announced it would be furloughing employees at some of its publications.

Additionally, the freelance community-cum-publication Study Hall published a very comprehensive piece on the failed promise of Civil. If I try to describe what Civil is in any great detail, I will butcher the explanation, but the gist is that Civil attempted to build a slew of newsrooms backed by bitcoin. They promised a new model for journalism, but ultimately weren’t able to succeed. One of the Civil-backed publications, Popula (which I subscribe to), is still up and running with a subscription model and a system for tipping writers, but only just barely. I highly recommend reading this piece.

And, finally, there was the whole Ben Smith vs. Ronan Farrow drama. I’m not going to get into it here, but you can read a wonderful digest of how everything unfolded in Delia Cai’s Deez Links newsletter.

What I’m Engaged With

Back in April, I wrote about one of my favorite types of pieces: the “what is the future of publishing?” article. It seems almost quaint to think that just a month ago I could have written about appreciating those types of articles. Now, it seems like more of a truly existential question to live through each and every day: What really is the future of publishing? And is there even one?

In the wake of all of the layoffs last week, that appears to be on the minds of a lot of media professionals.

First, there is Ben Thompson, who runs the newsletter/website Stratechery that covers “the strategy and business side of technology and media.” Last week, Thompson wrote a rebuttal to a piece by Ben Smith, the New York Times’s media columnist, covering the battle between Google and publishers over the need for Google to pay publishers to use their content. I covered Ben Smith’s piece last week and the battle between Google and publishers a few weeks ago.

I agreed with Smith, but Thompson has changed my thinking a bit. He argues that Google, Facebook, and other tech companies shouldn’t be paying publishers to use their content, that it actually should be the other way around—publishers should be paying for distribution. Dylan Byers, the senior media reporter at NBC News and MSNBC, also agrees with Thompson. I’m distilling here, but essentially what the two of them argue is that the journalism industry is broken and that this kind of fight, to have tech companies pay usage fees, is only a short-term and unscalable solution. Instead, media organizations need to adapt, they need to give up on whatever semblance of a business model still exists and find a new way to operate.

This conversation continued elsewhere on media Twitter. Jeff Jarvis, an experienced journalist and a professor at the CUNY Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism specializing in innovation in journalism, also agreed with Ben Thompson and detailed his thoughts in a Twitter thread. His thread concluded on the idea that journalism as a business needs to find a new way to market its value to the world.

Charlie Warzel, a writer at large for the New York Times and former BuzzFeed reporter, took issue with some of Jarvis’s wording. His argument boiled down to the fact that too often journalists and media professionals call for a new model for the industry, articulating it in lofty and idealistic language, without ever providing real solutions. Carrie Brown, also a professor at Newmark, backed Jarvis up and pointed out a few examples of how Newmark’s program is attempting to teach journalism students new skills and even tasks them with proposing and building new models for community-based journalism.

Over the past few days, it seems as though everyone is joining in this debate (or conversation, depending on how you want to spin it). Substack (yes, the very friends whose platform I use to create this newsletter) published a post on their blog addressing the topic and providing examples of media professionals who have used their platform to create small-scale but sustainable companies or revenue streams. Yet, there were journalists who astutely pointed out that even building a monetized brand on a platform like Substack presents its own issues.

And Study Hall, in one of their digests, openly called for the old ways to die. Their kicker was: “A friend who works in healthcare and is a communist told me that there is no normal to return to after COVID. He was speaking generally about the world, but I think this especially applies to us as media workers. The old normal was really bad! Why return to it? Time to build a new machine, starting from scratch, producing together a better normal for ourselves: self-sufficient and ready to rumble.”

So who is right here? I don’t know! Probably no one! Does it make sense for publishers to seek out some kind of licensing money from Google and Facebook? Yes. Does that help in the long run? Probably not. Will the subscription model work? Maybe, if you’re a big enough entity. Does a tipping system work? For some people, but that relies wholly on a person’s ability to build a premium brand that consumers would want to pay to have access to or support. Can smaller, local, subscription or donor-based models work? Maybe, but for how long? How many subscriptions can an individual pay for and keep track of? How generous can people be in what could be a prolonged recession?

All of these people are infinitely smarter and more experienced than I am, but most days, I find myself relating to the sentiment expressed by that quote from Study Hall. I relate to it because I believe that so much of what came before COVID, so much of our lives is over and changed forever. The way we work, the way we shop, the way we eat out, all of that and more.

As the 2020 election has approached, I keep thinking about the fact that we are now 20 years into a new century. Yet, still so much of what we do, so many of our leaders feel stuck in the 20th century. And that is true in the media industry. We are at the start of a new decade, set firmly in the 21st century, and yet so much of the 20th century remains. Maybe COVID-19 is the seismic event that pushes everything, all facets of our life, into this new century by necessity. Whether or not that is for better or for worse, or if the media as an industry can even survive, is something we’re going to have to find out.

A Little Bit of Culture:

Each week I end the newsletter with a brief ode/rant/riff on a bit of culture I’m passionate about. It might be music, it might be movies or TV, it might be a book, and sometimes it might be related to sports. Once a month, I’ll go a little longer on something.

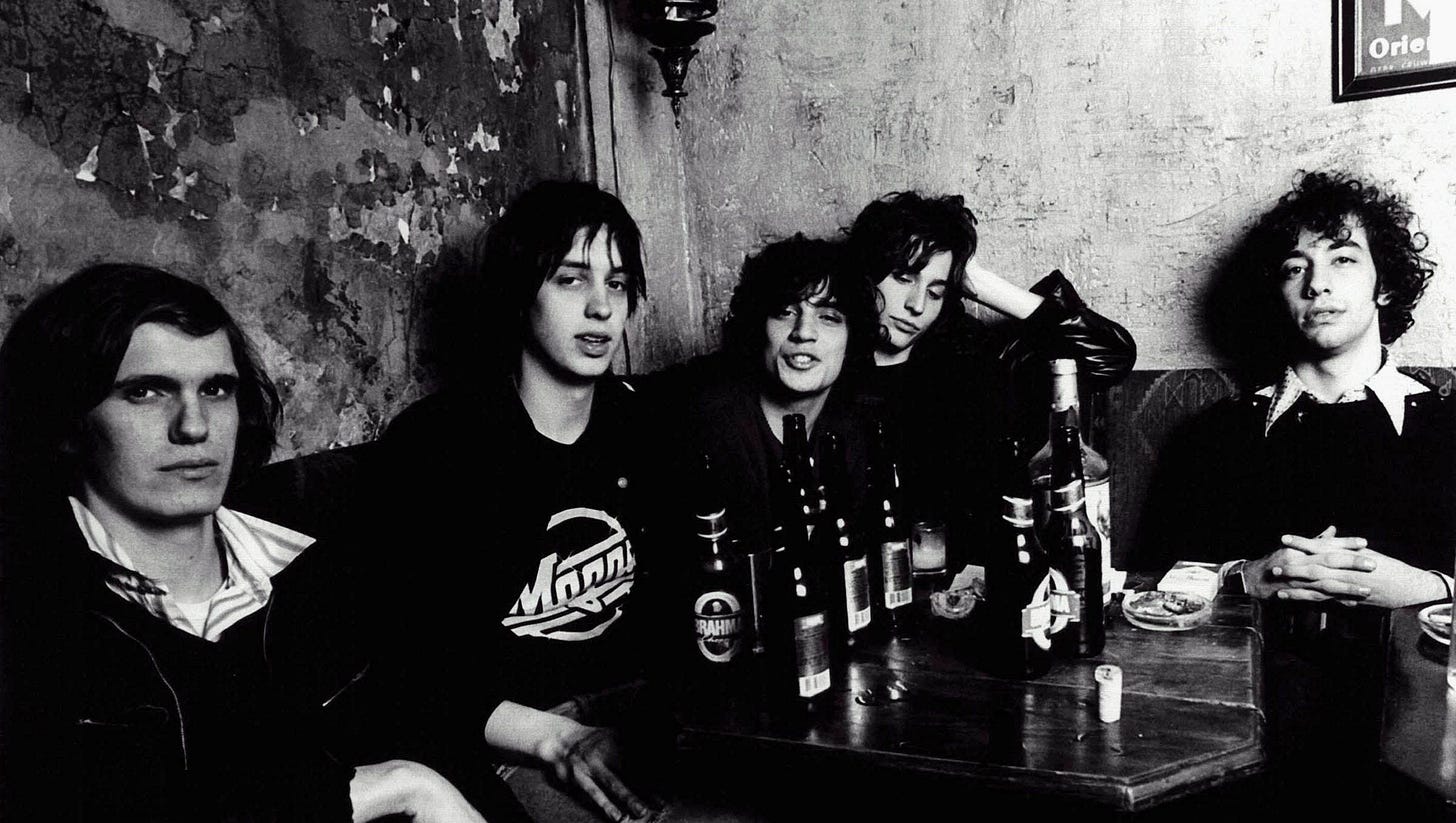

This week: The New Abnormal by The Strokes

It is nearly impossible for me to be objective when it comes to The Strokes. My history with them is so long now—I have been a fan since I was 16—and have believed in them, or wanted the best from them as a band for that entire time. And in believing, and in wanting, I’ve perhaps taken a blind eye to the actual quality of their music. Still, part of me does truly believe that each new release is as good as I think it is.

The Strokes’s latest album, The New Abnormal, came out in early April. It is their first record in seven years, since 2013’s Comedown Machine. I’d listened to the singles and had loved them the way I always love ever new Strokes release. So it was odd, then, that when The New Abnormal was released in its entirety that I didn’t exactly feel the same way.

The album has received near-unanimous praise (aside from Pitchfork) from critics and outlets I respect. Amanda Petrusich wrote in The New Yorker that, “The title is eerily prescient—a handy summation of how daily life in New York has changed since the beginning of the year … [The album] sounds better to me than almost anything else I’ve listened to this spring.” Stephen Thomas Erlewine, who is my favorite music critic, wrote in his newsletter that the album’s title “is strangely in tune with the early months of 2020, when nobody is quite sure what lies on the other side of the COVID-19 pandemic” and that The New Abnormal, “feels different from the rest of the band's catalog, a record filled with internal conflict and external cohesion.” AllMusic, where Erlewine writes but didn’t review this record, gave the album 4 ½ stars out of 5, saying: “Full of passion, commitment, and creativity, The New Abnormal marks the first time in a while that the Strokes have made truly exciting music.”

Reading all of this made me proud. Finally, after so many years of mixed reviews and being written off from ever being relevant again, The Strokes were being appreciated in a way they hadn’t been since maybe 2003.

However, the reviews felt hollow to me. The fact that critics were pointing to the album’s title as fitting and prescient for this current moment seemed to be lazy writing and observation. Does a phrase like The New Abnormal really feel that articulate or well-thought out, with or without the context of COVID-19? It sounds like the title of an album from a run-of-the-mill pop punk band circa 1998-2001.

The notes about lead singer Julian Casablancas turning his falsetto into a potent addition to songs rather than something to throw in felt true, as did the observations that The Strokes have leaned into texture, restraint, and complexity without bloat on The New Abnormal. But is this album really that much better than 2013’s Comedown Machine? Different maybe, but better, no. Not in my opinion anyway. The album lags in the middle, there are no thrilling moments of surprise like on “Welcome to Japan” or “Slow Animals,” and the record lacks the unbridled energy found in songs like “Partners in Crime” or “Happy Ending.”

It is a strange sensation for me to not fully embrace the positive reception of The New Abnormal. For someone who has been a Strokes “lifer” the fact that people actually like this new record should be something of a victory lap for me, a validation for all of the years where I argued with friends and anyone who would listen that The Strokes were still relevant, still making good music. If they didn’t like the new songs because they didn’t sound like Is This It? or Room on Fire, that was their fault, their own lack of imagination, not the band’s.

Instead of fully immersing myself in The Strokes’s latest album, I’ve found myself looking backward. After the album was released, I picked up Meet Me in the Bathroom, Lizzie Goodman’s 2017 oral history of the New York City music scene in the early 2000s.

The Strokes are arguably the protagonists of the book, since they were at the center of rock’s rebirth in New York City and their shadow loomed so large over indie rock in the first decade of this century.

The first time I read the book, I could barely make it through. I was in high school and college when most of the book’s main action occurs, and I didn’t experience the New York City scene first hand until its tail end. But I knew of so many of the characters, or knew people very similar to them, and had been to many of the landmarks of the scene, that it all felt a little too real for me. There’s a difference between reading an oral history about SNL in the 1970s or ESPN in the 1990s and reading one about people having sex at Union Pool or Lit in the early 2000s. And, to me, so many of the accounts and personalities documented in the book came off as so vapid and so hollow that it was hard to read without cringing.

Yet this time around, something about it seemed soothing. I thought of my perceptions of the bars and music clubs in the East Village, Lower East Side, and Williamsburg with fondness. My early adventures in New York City came flooding back to me vividly: the confusion of the train lines, the thrill of getting into a bar or club with a fake ID, the hopeless belief of finding love at a show, or the answer to life in a band or performance or a moment in time. That was perhaps when I had been most alive, most open to possibility—and now I was reading about that time, recalling adventures both first hand and second hand, from the comfort of a two bedroom apartment in South Brooklyn, leaning back in the comforts that an inconspicuous, but so far fortuitous career, can provide.

What struck me during this second read, was the fact that so many people believed in The Strokes while they were ascending. The feeling that they were the definition of a “band”—a group of guys with distinct personalities that you could identify with, aspire to, or attach yourself too, but also see as a distinct entity—was not just media hype, it was what the people who lived through it actually felt. The Strokes could never have been The Beatles, but they had a lot of the same ingredients, they hit the same beats. So, maybe they could have been The Beatles?

When Is This It? came out in 2001, so many teenagers who heard the record tried to start bands, tried to model themselves after The Strokes. I never had any musical ability, but I took a small amplifier and microphone, retreated to my bedroom and sang the songs out loud to an imagined audience, practicing my paces as a front man for a band I would never lead.

For a variety of reasons, The Strokes did not become anything that we imagined. They could only become what they were, which was always going to be disappointing compared to the stories that lived in the heads of anyone who was captivated by their music, by their charm, by their potential. In reality, Vampire Weekend or Animal Collective were the ultimate winners of the New York music scene of the early 2000s, their creative ability and desire to innovate and improve each so much stronger than The Strokes. Both of those groups also had the power of distinct individuality within the members of the band, but never to the same level as The Strokes. And though Vampire Weekend and Animal Collective each reached greater creative and critical highs, neither one grabbed the imagination of the audience in the same way.

What The Strokes were, and maybe still are, are the ghost of a trope that was marketed for decades. The idea of what an ideal rock band is and should be is dead and has been dead for a long time. No one truly cares about bands anymore—not in the same way that they once did. On a recent episode of the podcast “Music Exists” on the Ringer Podcast Network, Chris Ryan posited a theory that the energy that people put into using music or bands as a stand-in for their own individuality has now moved on to social media itself. You imagine yourself as a star through your presence online, you don’t need a band to inspire you to do that anymore. And, besides, there have been enough four or five white man bands in the rock canon. That time is over.

However, that trope is what I know and grew up on and will always be imprinted on my imagination. The Strokes were what I was trained to want from a rock band. And listening to them and seeing them play have given me some of the most memorable moments of my life since I started really caring about music.

I was there in August 2002 when The Strokes and The White Stripes played together at Radio City Music Hall. It seemed like no other bands, no other musicians existed in the world. It was as if The Beatles and The Rolling Stones had played the same bill in 1965 or 1966. The cultural importance was never actually that great, but it felt like it in the moment. I was 16 and drank too much on the LIRR and spent most of The White Stripes’s set throwing up in the bathroom. But I sobered up for The Strokes and watched a band captivate an audience in a way that made sense. I have never felt more like I was part of something than watching that performance. After the show was over, nearly the entire crowd idled on a closed-off 50th Street, looking up at the side of Radio City and waiting for Julian, Nick, Fab, Albert, Nickolai, Meg, and Jack to stick their head out one of the windows. And each time they did, the entire crowd cheered.

I was there in November 2002 at Roseland Ballroom when Jimmy Fallon and The Mooney Suzuki opened for The Strokes. On the line to get into the show my friends and I had met a few other kids our age who were seeing the band for the first time. Inside, we bumped into one of the kids, and he seemed to be in an almost a manic state of excitement. Later in the show, during The Strokes’s set, someone jumped off one of the balconies and into the crowd below. We learned later that it was that same kid who we’d briefly befriended. “He just lost it,” one of his friends said.

I was there in May 2014 when The Strokes, who hadn’t played a show in New York since 2011, were playing a small concert at the Capitol Theatre in Portchester, New York. I couldn’t get a ticket to the show, but I took the MetroNorth up anyway to visit a friend of mine who lived on the border of Rye and Portchester. I told him we’d get a ticket off StubHub at the last minute or, at the very least, just get drunk at the bar next to the venue. On the train ride up, I saw The Strokes’s Twitter account announce a ticket giveaway: Tweet your memorable Strokes moment and if we like the Tweet, you’ll get two tickets. I tweeted out the stories from my teenage years and waited in anticipation. My phone buzzed with a Twitter notification—but it was just a friend liking my tweet. Disappointed, I continued to check my phone, hoping for the best. But there was nothing. Two hours later, the show rapidly approaching, my friend and I were eating dinner in Portchester. My phone buzzed again. It was a Twitter notification from The Strokes account. I had gotten two tickets that I could pick up at the box office.

That Portchester show was the last concert I’ve been to where everyone in the audience could sing along to every song. Maybe that happens at Beyonce or Adele or Taylor Swift concerts. And maybe other pop stars or bands do ticket giveaways on Twitter that lead to last second miracles. I don’t know. But throughout my life, The Strokes have provided me with moments that just felt like what being a fan of a band was supposed to feel like—or was supposed to feel like during a time when bands actually did matter.

Nearly twenty years have passed since Is This It? came out. The Strokes were in their early twenties then. They’re all in their forties now. Bands from that era have lived full creative lives—some reaching true creative and critical peaks, some never getting off the ground, and others fading into obscurity after an initial time in the sun.

The Strokes have never had a neat narrative. Even when they were seemingly in the wilderness, they still played large international festivals and concerts. Even when they weren’t necessarily cool anymore, they still managed to remain cool in a certain way—unattainable, just out of reach. If you thought their new music sucked, they still retained some mystery because they never seemed to totally lose the potential they once represented. They’ve had periods where they’ve gone away, but they never entirely disappeared or faded out.

I think I’ve been looking to the past, feeling some kind of comfort in reading Meet Me in The Bathroom this time around, because so much of that book and the early rise of The Strokes came right after 9/11. New York was ground zero for America then in the same way it is during COVID-19. There is something reassuring right now about reading accounts of feeling like the world was ending and knowing that it didn’t.

Or maybe it's because I’m 34 now and music doesn’t mean the same thing to me as it once did. I sometimes long for the days when NME mattered, when Pitchfork really mattered, when finding out about a new song or album felt like it could change my life. But that’s not the case anymore. I like what I like and try to learn about and welcome new music the best I can. But I’m slower now, I can’t keep up. And I find it harder to be moved by music.

I’ve loved The Strokes from the start and always will. It’s just that now, maybe for the first time, I’m able to fully let go of what they represented—both in terms of music history and pop culture, and to me personally. I am what I am now. Just as The Strokes are what they are. The potential is gone, the myth making is gone, and the time for the ideas we once had about the way things could or should be are over.

And so The New Abnormal may be a mature and restrained record, it may be a creative rebirth, or it may be a poignant record for our times. I couldn’t tell you right now. Maybe ask me again in seven years.