Good morning.

This is going to be a long personal essay about a website called AllMusic.com and a particular music critic who used to write for that site. Its about those things and maybe a few others as well.

If that doesn’t sound like something you’d be interested in reading, feel free to skip.

As always: No hard feelings and see you next time.

Oh, and happy Halloween.

I.

On August 23rd of this year, I found out Stephen Thomas Erlewine reviews would no longer appear on AllMusic.com.

I’m going to use the name Stephen Thomas Erlewine a lot in this piece. So, before I go any further, I should say that Stephen Thomas Erlewine is maybe my favorite music critic. His work has appeared in Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, and a variety of other places. But I became a fan of his through his concise album reviews on AllMusic.

I learned about the end of Stephen Thomas Erlewine’s time writing for AllMusic on August 23 because August 23rd was a Friday and I was habitually checking, as I am known to do, the latest Editor’s Choice album reviews on AllMusic.

While checking AllMusic on my phone, I flitted to my email where I read a recent newsletter from Stephen Thomas Erlewine himself. In it, he mentioned how he had been let go earlier in the summer.

But I should clarify: Stephen Thomas Erlewine did not actually get laid off from AllMusic. He was laid off from a company called Xperi, which AllMusic.com licenses content from. Apparently, without my knowing, the way it worked was that Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote music reviews for Xperi and then those reviews were licensed or syndicated to AllMusic.com.

I, of course, realize that most of this is probably confusing to you. You’ve probably never cared about AllMusic. Most likely you’ve never even gone there.

You might’ve seen Stephen Thomas Erlewine’s name somewhere before—glancing at an album review on Pitchfork perhaps—but chances are it doesn’t ring a bell.

And, I can almost guarantee that you aren’t interested in finding out what the hell Xperi is.

I don’t blame you. But I care about all of this.

I care about all of this because the website AllMusic.com has been a part of my life for about 20 years now, which means Stephen Thomas Erelewine’s album reviews have been a part of my life for 20 years.

And the way that I learned about the end of his time writing for AllMusic.com, the manner in which it happened, and the very nature of what the site has become says something about the current state of the internet.

II.

If you read this newsletter then you probably recognize the name AllMusic because I reference it all the time in my playlist posts.

And there is also this kind of butchered Vice piece about it.

I don’t remember exactly when I learned about AllMusic.

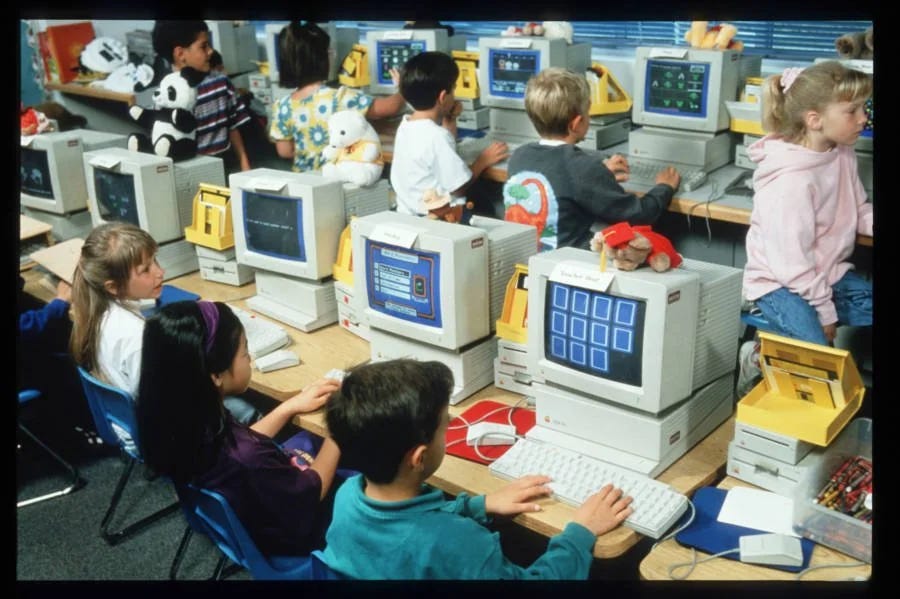

In the story of my life, I believe AllMusic entered around 2001. That’s after I’d already gotten heavily into Led Zeppelin, been to my first Phish show (Hartford, June 2000), and was devouring The Beatles Anthology (1995) on LaserDisc.

I’d also received The Book of Rock by Phillip Dodd (2001) as a Christmas present and would pore through each letter of the alphabet and read about every band whose name started with B or M or S. This helped me start to piece together all of the bands and records I had to learn about in order to understand the world around me. For some reason, I can still see the layout of the page for the entry on Beat Happening in my mind.

I would spend hours on the family Dell and download music from Napster or Kazaa and meticulously put together each album in a band's discography and burn CDs of every record.

And, in order to piece together the track listings and to make sure I was prioritizing burning the records in chronological order and then listening to them in the hierarchy of critical acclaim, I learned how to consult with AllMusic.com.

III.

Years ago, I pitched a story about AllMusic.com to the Letters of Recommendation column at the New York Times because it seemed like one of the last truly pure places online.

That pitch was rejected. (Rightly so—it was a thin idea.) But it turns out I barely knew anything about AllMusic at all.

According to Wikipedia, AllMusic was started by Michael Erlewine in the early 1990s as the All Music Guide, which was a 1,200 page guide book and CD-Rom.

Michael Erlewine seems to have led an extremely interesting life. He is described in different places as a buddhist, a computer programmer, an astrologist, a musician who hitchhiked with Bob Dylan in 1961, and a compulsive archivist.

Erlewine created AllMusic.com, AllMovie.com, and AllGame.com as website databases to document as many of the existing works in those different mediums as possible.

He hired his nephew, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, in 1993 to help develop editorial content for AllMusic.com. And by 1996 he sold the properties to a company called Alliance Entertainment Corp. That company filed for bankruptcy and in 1999 AllMusic.com was purchased by Yucaipa Equity Fund. Wikipedia says that around this time AllMusic had cataloged over 350,000 albums and over 2 million tracks.

By 2007, AllMusic.com was purchased by TiVo Corporation. In a Detroit MetroTimes article from that year, Brian J. Bowe painted a picture of the AllMusic offices at that moment in time.

Here, in this soulless part of town, sits a soulless-looking edifice that appears to be some sort of light industrial complex. But this, the world headquarters of Internet giant All Media Guide, is more like the most gargantuan reliquary of pop culture imaginable.

Inside that 32,000-square-foot building, a staff of 150 well-trained media and technology geeks set about the task of obsessively cataloging every piece of music, every movie and every video game ever produced. It seems like a Sisyphean task, but after 15 years, the company has amassed an amount of data that's difficult to describe. Consider the following:

Deep within the bowels of AMG headquarters is a locked-down room that would make any record geek's knees go weak. Inside that room is the AMG archive. It's 7,000 square feet of cabinets, with boxes stacked on top of cabinets. A whiteboard keeps a running tally: as of Jan. 12, the archive was home to 461,550 albums (multi-disc sets count as one album), 75,259 DVDs and 3,477 games.

And those are just the physical items AMG owns. The growing database at the moment holds information on more than 8.5 million songs and 900,000 individual albums. If an individual song clocks in at three minutes, it would take 25.5 million minutes to listen to all of those songs — and that computation ignores longer tunes like "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" and the works of Fela Kuti.

Bowe’s piece goes on to describe the AllMusic staff’s work as, “[adding] formal data like artist names and titles as well as descriptive content about genre and style…bylined reviews, biographies and ratings, as well as data about similar products and influences.” The story also cites the website has having “monthly page visits” of “120 million views.”

By 2015, AllMusic had been purchased by something called BlinkX, which became RhythmOne. In 2019, that company was purchased by something called Taptica, which was rebranded in 2020 as Tremor International and then again in 2023 as Nexxen.

Per Wikipedia, Nexxen is a company that “developed an application that analyzes cell phone users' behaviors, spending and how the previous relate to demographic data such as age, gender and location, with the data then being used by advertisers. Nexxen sells advertisements based on complete transactions, such as registering for a game.”

But if you go to the AllMusic.com site today, at the bottom it reads: ©2024 ALLMUSIC, NETAKTION LLC - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

On the Netaktion about us page, the company is described this way: “With an internal capability of reaching the appropriate market across various media channels in over 25 countries and access to 81% of U.S consumers, we are able to bring in new customers beyond the regular scope of most other digital agencies, with minimum risk.”

But on AllMusic when you read their FAQ and look at the entry for “Can I write for AllMusic?” you see the following.

I’m going to be honest: After following all of these threads, I have no idea who actually owns AllMusic or how the content gets on their website.

But this transformation of a database website into a kind of Frankenstein’s monster of content and ownership and licensing depresses me.

IV.

When I heard about Stephen Thomas Erlewine being laid off, or that his reviews would no longer appear on AllMusic, I poked around for more information.

I found a page on the AllMedia Network support forum where a user named Nathan Dean wrote the following:

Ironically on the very day I renew my Allmusic subscription, I learn you've laid off Stephen Thomas Erlewine. The site has less coverage of new music than ever before and barely limps along in functionality. Thankfully, there are still places like Acclaimed Music forums that are actually interested in serving their audience. I doubt this site lasts the length of my subscription, and am not sure I'll care if it doesn't. (Also, funny enough, I haven't had to work this hard to leave a comment since the internet was dial-up.)

To which someone named Zac responded:

Let me correct you. We have not laid off Stephen Thomas Erlewine.

We license our information from a company called Xperi and they made the aggravating and, in my opinion, foolhardy decision to lay him off.

We will miss receiving his reviews in our data feed. As a friend of his for 24 years I know he will land on his feet, but we will certainly miss his writing.

To which the user Nathan Dean responded:

If that is the case, the information you license from them has degraded to the point of absurdity. As I implied in my original post, if you can't be better than a fan generated content site, what's the actual point in continuing to exist. This isn't really about the layoff so much that as night follows day, the decline in Allmusic has been so consistent as to be completely predictable. Maybe in the next year things improve and I'll be proven wrong, nothing would make me happier. I've gone from a user who would look at new music reviews on release day to someone who always waits a month to give time for reviews to populate. I don't mind that when there is new and surprising content, it's well worth the wait. Unfortunately the new content gets thinner and thinner and the usability of the site is so bad that I can't imagine a new user saying "This is great, need to subscribe to this." I'm a long time user and still have the old printed album guides on my shelf and it saddens me to see this decline. Thanks for listening.

To Nathan Dean, I can only say: I hear you—and your concerns reflect the larger state of the internet, brother.

To Zac, I can only say: You’re doing the Lord’s work in the community, brother.

And I have to agree with Nathan on the fact that as AllMusic switched hands from owner to owner the quality of the website did seem to decline.

There were times over the last five to ten years when AllMusic was barely usable on mobile. Review pages would refresh several times before you could read a 300 page review, ads would pop up and take you to other pages—it was all just kind of a mess.

It works OK now, but who knows how long that will last.

And who knows how long I’ll go to the Editor’s Choice page every Friday or how many times I’ll ease myself to bed reading a random Paul McCartney or Tom Petty or or Diana Ross or White Stripes record or track review on AllMusic.

That’s not really because of the website’s usability. It never was. That’s because there won’t be any new Stephen Thomas Erlewine reviews there. And that doesn’t feel right.

V.

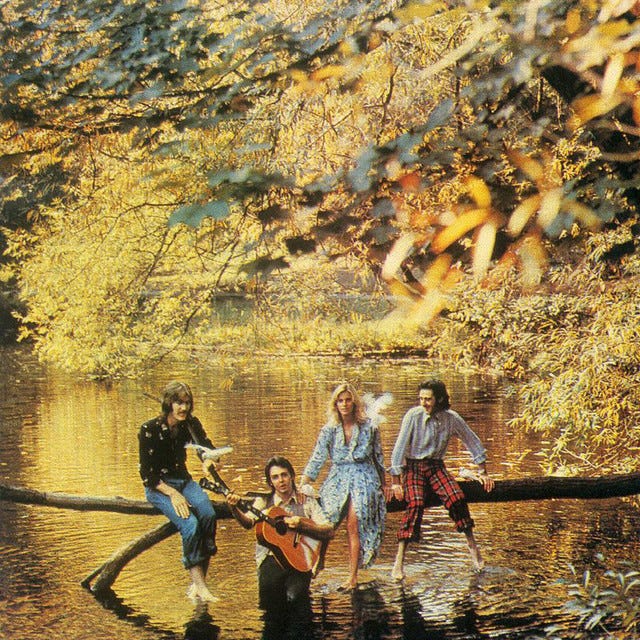

I realized Stephen Thomas Erlewine was my favorite music critic after reading his review of Wild Life (1971) by Paul McCartney & Wings for maybe the fifth time.

To me, it remains the most concise bit of music criticism that also manages to say so much. The review is 246 words total. And these 136 words paint such a clear picture of a musician at a certain time in their life and career as well as a critic engaging with a single body of work within the narrative of that artist’s career.

[T]hat's what makes this record bizarrely fascinating -- it's hard to imagine a record with less substance, especially from an artist who's not just among the most influential of the 20th century, but from one known for precise song and studiocraft. Here, he's thrown it all to the wind, trying to make a record that sounds as pastoral and relaxed as the album's cover photo. He makes something that sounds easy—easy enough that you and a couple of neighbors who you don't know very well could knock it out in your garage on a lazy Saturday afternoon—and that's what's frustrating and amazing about it. Yeah, it's possible to call this a terrible record, but it's so strange in its domestic bent and feigned ordinariness that it winds up being a pop album like no other.

There’s so much life in that review. Not only does it reflect Erlewine’s life listening to music but also reflects the many lifetimes that Paul McCartney lived and especially the life he was leading in the early 1970s as he tried to piece his identity together away from The Beatles.

It is empathetic and forgiving. But it is also critical and cutting at the same time. And yet it’s never snarky or snide.

Stephen Thomas Erlewine has thousands of reviews on AllMusic that are that good or, depending on your taste, maybe even better.

Whenever I’d read a review of an old or contemporary record, chances are I’d look up at the top of the review page and the byline would be from Stephen Thomas Erlewine.

As you can see from those comments I found on the support forum, I wasn’t the only one who associated AllMusic.com with Stephen Thomas Erlewine.

On the Steve Hoffman Music Forums (a message board for music nerds and audiophiles) random people commiserated over the end of the Stephen Thomas Erlewine era at AllMusic. A user named zphage wrote, “Crazy, I always thought he WAS Allmusic. Probably replaced by his own body of work, which AI can now glean from to create new reviews.”

And a user named IHeartRecordsAz basically summed up my experience with AllMusic.com and my teenage years discovering music.

“When I started to explore music outside of my comfort zone in middle and high school (between 1997 and 2003), Allmusic was one of the places I'd go to read reviews and learn more about artists I wanted to explore and listen to. When I started getting into grunge music at the start of high school, part of what attracted me to the genre was the lore of the genre that was encapsulated in reviews and profile photos on the site, and when I wanted to find similar artists to Pearl Jam or Soundgarden, Allmusic is where I learned about Mudhoney and Tad. When artists like Jane's Addiction, Led Zeppelin and The Velvet Underground finally clicked for me senior year and the summer after, AllMusic and Stephen's reviews were a valuable resource as to where to go next; when I checked out an album in my school's public library, AllMusic was where I'd go after an album like Neil Young's Decade captivated me; when I bought Rolling Stone's 500 greatest albums of all-time issue in 2003 and an artist like Big Star or The Flying Burrito Brothers peaked my curiosity, AllMusic was where I'd go to learn more; when I finally gave Dylan a chance and heard he could rock as hard as any grunge act after popping Live 1966 in my car's CD player, AllMusic was one place where I read up to see what else I had missed about him; and when I would go to Arizona State's record store to buy a Big Star album, and I saw a bunch of Phish CDs that peaked my interest, I went to AllMusic to see if they were a band worth exploring. Basically, Stephen's AllMusic reviews had as big an impact on this Xennial as Robert Christgau and Lester Bangs did other generations, but it does feel like the end of an era a bit, and it's going to take awhile for it to sink in that, even if I can read his work other places, he won't have a presence there anymore. Here's hoping he gets picked up and receives steady work somewhere else.”

Those last few sentences especially ring true to how I’m feeling. Stephen Thomas Erlewine is not dead. He just reviewed Leon Bridges’s new album Leon for Pitchfork in October.

But for those weird music history obsessives like myself, something feels different now that he’s not formally associated with AllMusic.com anymore.

VI.

So much of what I associate the internet with is the feeling of discovering that there were places online where I could get access to hard to find pieces of culture like Dragon Ball Z and that there were people all over the world drawing and writing fan fiction about it.

Or that there were entire communities devoted to pretending to be professional wrestlers and writing short one act plays and entire wrestling events in a script format to entertain a bunch of strangers you spoke to in AOL chat rooms or glowing AIM windows.

Or that there were places where I could discover inventive pieces of writing that inspired me to find my own voice on the internet—even if that meant I was starting on a journey where I’d be speaking into a void of neverending content and focusing on something I most likely wasn’t even very good at.

And when I discovered each of those things, I felt as if I was opening a door into a new room of a house for the first time.

That’s because I was discovering passions between the age of 14 and 25. And the internet was becoming the main portal for discovery.

But as Roger Sterling said: “What are the events in life? It’s like you see a door. The first time you come to it, you say, Oh, what’s on the other side of the door? Then you open a few doors. Then you say, I think I want to go over that bridge this time, I’m tired of doors. Finally you go through one of these things, and you come out the other side, and you realize, that’s all there are, doors, and windows and bridges and gates and they all open the same way and they all close behind you.”

All of those doors on the internet closed behind me for one reason or another. And, to me, on a lot of days the internet itself sort of feels like another closing door. But that might just be the way I feel as I’m getting older and nearing the end of another election year.

One of the doors that always seemed open was AllMusic.com. It was the place where I could go read Stephen Thomas Erlewine reviews or Richie Unterberger reviews as part of this massive encyclopedia of music.

It’ll still be there, still recognizable even if a lot of the writers that built the database are no longer adding well-crafted assessments of albums. It’ll still be there though it's hard to know how the reviews are even getting written and put onto the website at all.

And Stephen Thomas Erlewine will still be writing reviews for music publications and running his Substack and trying to support a career and a life like so many other writers and editors in the world.

But with each passing day, AllMusic will feel like another place on the internet that used to be great but isn’t worth visiting much anymore.